Full Fibre by 2025: A Bold Vision or a Failure to Grasp Reality?

CW was joined by a former CTO of Ofcom, Stephen Unger, and a consultant behind the Frontier Economics report upon which Labour has costed its latest policy. Despite being in the grip of election season, both speakers left politics to one side and focused on the real questions being asked: is nationwide full fibre by 2025 a sensible policy, and is it possible to deliver?

Martin Duckworth approached the question with an economist’s hat on. Before Frontier Economics, he worked as a civil servant in multiple departments, including for Oftel during the liberalisation phase of 1998. Over the past ten years a lot of his time has been spent assessing the virtues of full fibre rollout. Stephen was up until recently a Board member of Ofcom, setting regulatory strategy for the UK, representing Ofcom internationally, and leading Ofcom’s research programmes in both technology and economics. Here’s what they had to say on the subject (please note that their views are their own rather than of their respective current of former employers).

Are you interested in this subject? Consider CW membership to get free access to events, resources and contacts in the UK’s fixed and wireless internet market.

Fibre Supply

It’s taken about 100 years to get a copper line to every country in the household. Roughly 50% of households in the country receive their internet from early 20th century infrastructure which used to be state-of-the-art, but isn’t any more. It’s been modified consistently over the years to deliver an okay service, but the reality is that it is outdated. The other half of the country are supplied by hybrid fibre-coaxials (HFCs), a combination of optical fibre and coaxial cable. Even this isn’t state-of the art.

Ideally, the nation would be run on fibre. It is far more resilient than copper networks, able to endure environmental interferences from – for example – water. Fibre networks typically see half the fault rates of copper networks. It is cheaper to roll out and operate. It is fundamentally passive whereas fibre to the cabinet (FTTC) and HFC still needs power. And, for consumers, it is more predictable – your data speeds are more consistent, and your provider is able to inform you far more accurately about what level of service you can expect.

The layout of the current network has flaws. Martin likened it to the train network: built around terminals (and their ensuing bottlenecks) rather than a continuous flow of traffic through an area. However, it is hard to justify shifting to an entirely new architecture when infrastructure is already in place, even if the proposal does offer significant benefits. In the case of fibre broadband, the implications of installation are vast and include drilling through the walls of millions of private homes.

Despite this, Stephen pointed out that in 2016 the Government decided that the time had come to move from copper to fibre networks. In 2018, politicians set easy to reach targets: fibre to 15M premises by 2025 and nationwide by 2033. With these numbers, there was good engagement from operators. Openreach, for example, launched their “fibre first” policy.

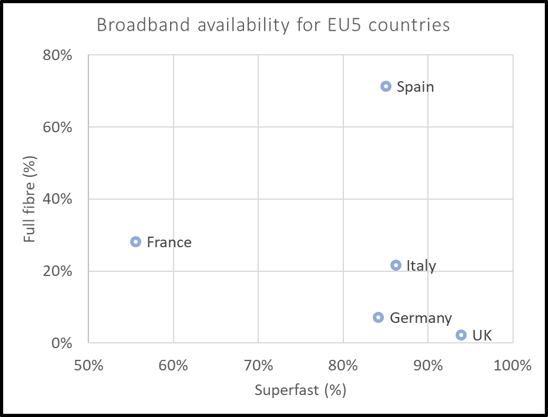

This year, policies have changed as has the messaging coming from Government. We are hearing that the industry has failed consumers in delivering high speed internet to homes. This is not necessarily the case – at 95%, the UK has the highest rate of superfast broadband availability of the EU5; but at the same time our full fibre rate is the lowest. Is this really a problem?

Broadband coverage in Europe 2017, Report to the European Commission by IHS Markit and Point Topic

The UK has had the capability for deploying full fibre for thirty years. Back in the early 1990s BT deployed a passive optical network in Bishops Stortford which was very similar to infrastructure being installed today by Openreach. The problem was that at the time the use cases didn’t exist for fibre; television was the only application for which it was sensible. Now the internet landscape looks very different.

Stephen is clear to emphasise that the status of the UK’s broadband network today is the result of a conscious choices made by previous Governments and operators, rather than neglect or lack of investment. Prioritising full fibre over superfast broadband would have delivered a premium service to a few at the cost of the many – as has been seen in other countries. France, for example, in 2017 had a 28.3% full fibre rate but only 55.5% superfast. The UK made a choice, and has delivered exceptionally well on it. The fastest way of making services widely available was to deploy advanced signal processing on the copper network.

Fibre Demand

The basic supply-demand model states that if people want something, someone will supply it. So why is the Government intervening in this matter?

Sometimes Governments interfere when consumers aren’t aware of what might be good for them – in the case of faster broadband, you may need to experience it to want it, otherwise if you’re able to hold a Skype call and stream a Netflix episode without interruption, you might think that you are fine without. Sometimes they interfere when there is an imbalance of market power, where despite the demand being present a monopoly supplier may decide that it doesn’t need to incur the costs of delivery. However, in this instance, it’s more because the Government perceives that a full fibre network will deliver a larger socioeconomic impact than simply the sum of benefit delivered to individual consumers. It believes that fibre will increase national productivity and maintain the UK’s economic position in the global market.

Is this the case? Martin says that economists have tried to find causation between full fibre networks and an increase in GDP, but evidence is mixed and while correlation is clear, causation is not. Take for example the United States and Germany, two nations without high rates of fibre who are thriving economically.

Potentially, the Government is forward thinking and expecting the increase in productivity to come from a yet-to-be-deployed application. However, Frontier Economics did some work for the National Infrastructure Commission on this subject and concluded that only if future demand is at the highest end of predictions would the copper network not be enough. It is far more likely that the existing copper network will suffice; many of the futuristic applications that are being heralded by 5G (telemedicine, telemuting) were expected to emerge in the late 1990s following the development of the “information superhighway”. They didn’t, and Martin believes that we are still a long way off these applications being mass deployed now. In his opinion, there is little evidence of impactful externalities that would warrant nationwide full fibre. He feels like politicians are confusing the need to bring everyone up to a good enough level and delivering the fastest possible speeds that we can.

Intervention in the Fibre Market

No country’s broadband market will ever function perfectly. There are extremely high barriers to entry, as well as high operating costs. However, in the UK about half the country (the more populated geographies) are in an area with acceptable competition with Sky and Virgin Media offering services alongside BT. The other half has Openreach as the monopoly provider. Despite Government intervention, the outcome for consumers will never be the best on the market.

The challenges with Government intervention are twofold. Firstly, you need to properly define the problem that you are trying to solve. Secondly, you need to identify an effective remedy that minimises unintended consequences.

The UK’s fibre upgrade is arriving rather late to the international internet party and in many ways this is a good thing. It allows our politicians and civil servants to learn lessons from how other countries have addressed the same issue. Some have done well, more have struggled.

For example, in 2008 Australia attempted to build a national fibre network. They allocated funding, and opened a call for applications. The only response came from the incumbent supplier, who (according to Martin) put little effort into the process. In response, the Government nationalised the sector and tried to install full fibre nationwide. It is currently one of the worst performing OECD countries for broadband performance.

In somewhat similar scenes in 2012, Ireland established a national broadband plan for areas that wouldn’t otherwise receive good service due to competition failings. Seven years later the contract has just been finalised with the selected supplier at three times the cost originally allocated for the scheme after Eir and Vodafone pulled out of the selection process, enabling the last company standing to demand whatever they wanted for delivery.

It’s not all bad news for Government intervention in the fibre market. New Zealand has exceptional fibre rates for a very rural country; it managed this by forcing incumbents to structurally separate and bid for franchises. Spain has a high rate of fibre because of its policy of regulating infrastructure and the placement of equipment on buildings but deregulating pretty much every other aspect of the market. A sensible conclusion would be that if the current market isn’t working, first ask what you would like to achieve; then consider why the current market isn’t delivering this. If intervention is necessary, be very clear on your objectives from the outset and be wary of unintended consequences.

What’s currently being done in the UK?

Stephen outlined the policies being acted on in the UK to build a full fibre network. These include:

- In 2018, the Government negotiated a new structure for Openreach as a legal entity to BT in order to create an organisation more focused on its customers and investment in fibre.

- By requiring Openreach to open its ducts and poles to other suppliers, the Government has stimulated more competition in an imperfect market.

- There has been a lot of consideration on pricing in order to make it more attractive for competitors to lay their own fibre rather than purchase from BT.

- A minimum limit of 10MB/s has been prescribed for the country and anyone receiving less than this can request a better connection.

Early indications are that these policies are stimulating the market and accelerating the fibre rollout. Openreach is currently installing fibre to 1.2M homes per year and Stephen expects this to scale to about 3M per year when the process is more understood and settled. Admittedly, the last 10% of homes will be challenging, but at this rate all 29M homes in the UK could receive fibre within the next ten years. However, to achieve the goal of full fibre to every home by 2025 is not possible under current plans. The rate of deployment would need to increase, and at that point the UK would hit a labour shortage of skilled staff. Operators are already doing what they can to train engineers, but to hit targets in that timescale the UK would need to attract EU labour which, in the current political climate, is unlikely to happen. Changes to town planning regulation would also be necessary so that operators can more readily dig up streets, and that is a politically sensitive area to take on.

Closing thought

The choice for the country is not full fibre or nothing. The UK already has very high penetration of superfast broadband, and the consumer demand for full fibre as a solution is low. The question politicians face is: should full fibre be a priority investment area over other sectors? Is it a more pressing issue than public transport, or the NHS? Both speakers agreed that a good fibre network in the UK should be a target; but not at the cost of nationalising the industry or setting timescales that would require a magnitude more investment and political capital to achieve.