UKIPO issues guidance on protecting AI innovations

In September 2022, the UK Intellectual Property Office (IPO) published guidelines setting out the practice within the IPO for the examination of patent applications for inventions relating to Artificial Intelligence (AI).

This guidance follows the government’s response to a call for views on AI and intellectual property, which committed the IPO to publish these enhanced guidelines for the examination of patent applications for AI inventions. Our article reporting on the response to the call for views can be found here.

AI guidance is provided in two parts. A first document found here sets out the legal framework for examination of AI inventions and how this will be applied by the IPO. A second document found here helpfully provides a number of example AI inventions along with a simplified assessment of each invention to provide an opinion as to whether each invention is patentable.

The documents combine to provide useful guidance with practical examples as to how AI inventions are to be examined by the IPO.

A summary of the published guidance is provided below.

What is an AI invention?

For the purposes of the guidance the IPO has categorised AI inventions generally into two main categories:

- “applied AI” in which AI techniques are applied to a field other than the field of AI; and

- “core AI” in which applications or use-cases of AI are not specified, but a core AI invention is instead defined by an advance in the field of AI itself (e.g. an improved AI model, algorithm or mathematical method).

Other aspects of AI are considered in addition to the above since AI inventions require training. AI models or algorithms may be trained using specific training datasets, for example. More information on training and datasets is provided below.

Exclusions to patentability

UK patent law excludes from patent protection inventions relating solely to a mathematical method, a computer program and/or a business method.

AI inventions typically rely on mathematical methods and computer programs in some way. Despite these exclusions from patentability, AI inventions may constitute patentable subject matter if a task or process performed by an AI invention makes a technical contribution to what is already known.

When does an AI invention make a technical contribution?

The guidelines broadly consider that an AI invention may make a technical contribution, and therefore be allowable, if:

(1) a task performed by a program represents something specific and external to the computer and does not fall within one of the exclusions from patentability. In this context, and more specifically, an AI invention makes a contribution that is technical in nature if its instructions:

o embody a technical process which exists outside the computer; and

o contribute to a solution of a technical problem lying outside the computer;

(2) a program that solves a technical problem relates to the running of computers generally to make the computer work better. In this context, a program can make a technical contribution if its instructions:

o solve a technical problem lying within the computer itself; or

o define a new way of operating the computer in a technical sense.

(3) a program’s instructions define:

o a functional unit of a computer being made to work in a new way; or

o a new physical combination of hardware within the computer, provided that the instructions produce a technical effect within the computer that does not fall solely within one of the exclusion from patentability.

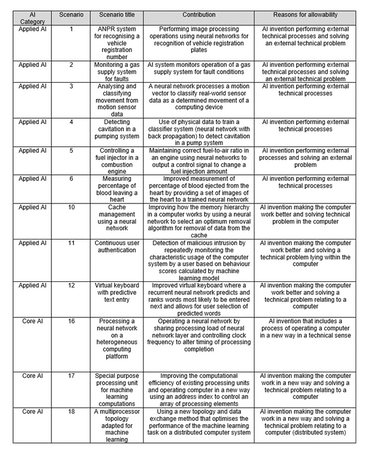

Patentable AI example scenarios considered to make a technical contribution

Non-patentable AI example scenarios

Scenarios 7 to 9 provided as part of the guidance are examples of “applied” AI inventions that are considered not to make a technical contribution and therefore are not patent eligible. Invention examples in these scenarios concern automated financial instrument trading, analysis of patient health records, and identification of junk e-mail using a trained classifier. These are considered excluded from patent protection because they relate to a business method or a computer program that merely processes information or data without revealing a technical contribution.

Scenarios 13 to 15 are examples of “core” AI inventions considered not to make a technical contribution. These scenarios concern optimisation of a neural network, avoiding unnecessary processing using a neural network, and active training of a neural network. These are considered excluded from patent protection because they relate solely to a computer program that does not solve a technical problem or merely processes information or data without revealing a technical contribution.

Training AIs and datasets

For the purposes of the guidelines, methods of training and other machine learning methods may also be categorised as “applied” AI or “core” AI, and they should be examined in the same way as described above.

Inventions relating to training AIs are compared to calibration since technical devices or functions may require calibration before they can be used accurately for their intended technical purpose.

Computer-implemented methods of calibration are patentable if they make a technical contribution. And by analogy, a method of training an AI model or algorithm for a specific technical purpose may also be considered patentable.

A dataset may be considered patentable by virtue of it being an integral feature of a patentable training method/algorithm or in the method of generating or improving the dataset, where the method makes a technical contribution. The dataset itself (dataset characterised by its content or delivery) is unlikely to be patentable.

Scenarios 4, 6, 11 and 18 provide examples of patentable inventions to training AI models or algorithms. An example of a training method not revealing a technical contribution (i.e. not patentable) is set out in scenario 15.

Sufficiency

The guidelines reinforce the importance of describing the AI invention, including the training dataset, in sufficient technical detail so that the invention can be performed by someone skilled in the art without undue burden. This has been set out in UK case law, Eli Lilly v Human Genome Sciences [2008] RPC 2, and the IPO considers these principles to be consistent with a recent decision of the European Patent Office’s (EPO) Board of Appeal, T 0161/18.

In reason 2.2 of decision T 0161/18 the Board stated that:

the application does not disclose which input data are suitable for training the artificial neural network according to the invention, or at least one dataset suitable for solving the present technical problem. The training of the artificial neural network can therefore not be reworked by the person skilled in the art and the person skilled in the art therefore cannot carry out the invention.

It should be noted that, in T0161/18, the training of the neural network was a feature of the claim and required to differentiate from the prior art. The requirement for a sufficient disclosure of the claimed invention is a fundamental requirement of patent law that applies equally to AI-related inventions.

Conclusion

These guidelines provide a useful overview of the IPO’s practice on assessing AI inventions by combining legal guidance with a number of scenarios of AI inventions to demonstrate the possibility of patent protection for AI innovation in the UK.

We look forward to applying the guidance while we can continue to assist our clients in obtaining valuable protection for their AI inventions.